Whilst the popular focus is on the politics of the US, as investors in companies it is useful to remind ourselves that various US governments have interfered in corporate America’s ability to generate profits over the past century and all have failed. The reason for writing about this now is that the US equity market has reached new highs this week even whilst the US President’s attack on the US Federal Reserve’s independence has reached new heights. Remember that the US central bank is in practice ultimately the banker of last resort to the world.

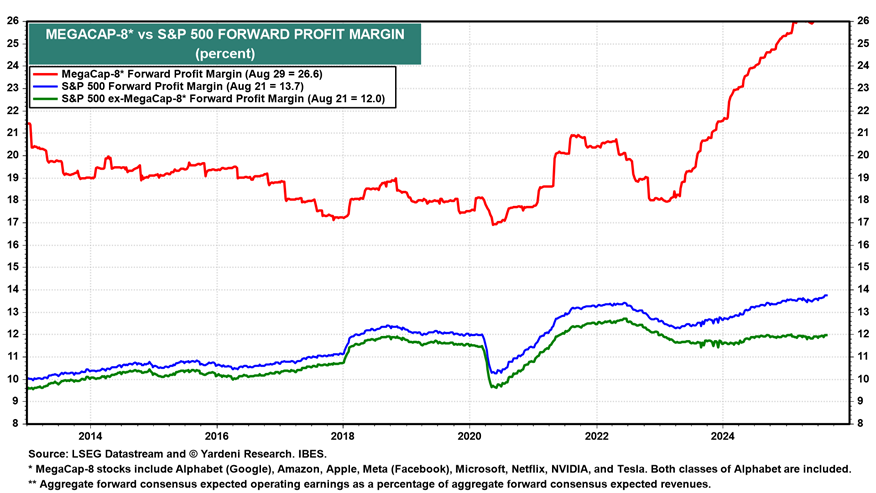

Consistently, a selection of US companies have exhibited a remarkable power to generate supranormal profits even during a period of extreme global geopolitical shifts. The chart below illustrates how the eight largest US technology companies red line) have continued to generate higher profits than the other 492 MegaCap companies (green line) over the past decade even with the headwinds of higher interest rates, tariffs and proxi-wars between the US and China.

Source: Yardeni Research Inc, Stock Market Briefing: The MegaCap-5, 1st September 2025

Now, the lazy narrative is that these companies are trading at very expensive valuations and therefore investors should look to diversify into the ‘other’ US companies as they are trading at lower valuations than the largest eight technology companies. But, what if something different is going on and these companies can in fact maintain higher growth rates and profits than the rest for the coming 20 years: what then?

To consider this we must consider a historical example: the Nifty 50 of the 1970s.

The Nifty Fifty in the 1970s and today’s MegaCap 8 technology stocks both represented the dominant, most admired companies of their eras, drawing investors eager for growth and perceived stability. Yet each group carries lessons about concentration, valuations, and investor expectations.

The Nifty Fifty were known for consistent earnings growth, blue-chip reputations, and wide moats, much like today’s MegaCap tech firms. Both groups attracted the label “one-decision stocks”—just buy and hold. Crucially, investor optimism pushed their valuations well above market averages: Nifty Fifty stocks regularly traded at very high P/E multiples, ignoring cyclical or valuation risk, as many investors saw them as immune to downturns. Today’s MegaCap 8 (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia, Tesla, and Netflix are priced for continued high growth, reflecting their market dominance and technological leadership. Like the Nifty Fifty, their outsized success has driven index concentration and crowding.

There is a difference this time, however.

The Nifty Fifty stocks of the early 1970s were famous for trading at very high average price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios—around 42x earnings at their peak in 1972, more than double the S&P 500’s P/E of about 19x at that time. Some individual Nifty Fifty components, like Polaroid or McDonald’s, saw P/Es as high as 60–95x.

In contrast, the current MegaCap 8 technology stocks tend to trade at P/E ratios mostly in the 25x–70x range. For example, recent trailing P/Es are approximately: Apple (34x), Microsoft (40x), Alphabet/Google (29x), Amazon (56x), Nvidia (72x), Meta (29x), and Tesla (59x), with some variation by company and forward estimates.

Overall, while both groups were significantly more expensive than the broader market in their era, the Nifty Fifty’s peak multiples were, on average, somewhat higher and driven by an even broader consensus that their growth would be perpetual. The MegaCap 8’s valuations remain elevated, but they have experienced periods over the recent past when investors have derated individual companies significantly if they have not met expectations, a positive sign.

This variance in valuations today, alongside the number of events that could have derailed their profitability over the past decade, leads us to err on the side that something is different this time around. This does not change the fact that as they are trading at higher valuations than the market average, they are susceptible to meaningful corrections in price when investors get nervous more generally and this is one of the reasons why they should form part of your equity allocation, but not the majority.